Pop art spoke to the maintenance of the capitalist economic structure by affirming capitalism as an economic ideology through business practices and commercial reproduction techniques, like silk screening and direct appropriation. In this sense they were notably antithetical to the Marxist, hippie, current of thought that had also been in vogue during the 60’s. In his book, “The Philosophy of Andy Warhol”, Andy Warhol talks about the relationship between art and business in the 60’s.

“Business art is the step that comes after Art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. After I did the thing called “art” or whatever it’s called, I went into business art. I wanted to be an Art Businessman or a Business Artist. Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. During the hippie era people put down the idea of business—they’d say, ‘Money is bad,’ and ‘Working is bad,’ but making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” (Warhol, pg. 92)

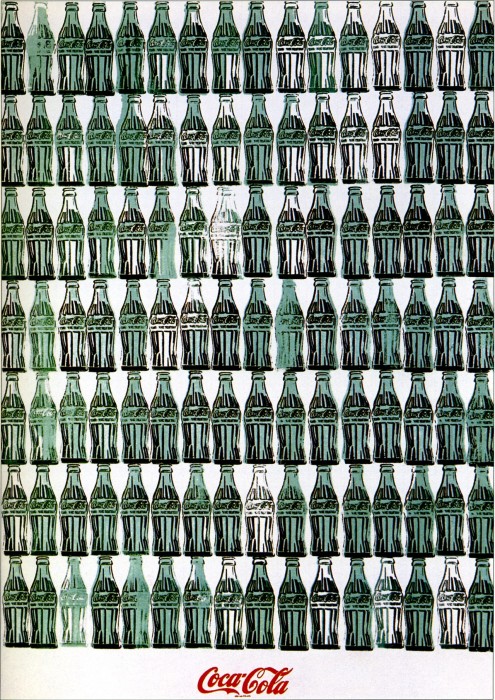

The “Green Coca Cola Bottles” (1962) painting is a standard ‘business art’ work that was produced by Andy Warhol. Many people were not a fan of Warhol’s business attitude. They saw it as commodification of art, changing art into mere products for the marketplace, to be bought and sold. Art critics in the early 60’s, certainly saw pop art as a threat to art in general, or at least to their sense of ‘high’ art culture.“Pandering to lowest-common-denominator tastes, kitsch threatened to eradicate high culture by seducing away its audiences- as well as artists themselves. This development imperiled the distinction between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, between art and commodity.” (Doris, pg. 19) While many people disliked pop art precisely for the reason that it was supportive of capitalism and catered to the mass culture, this may be one of the main reasons for its great success. It was art that was accessible to more people and easier to understand than previous movements such as abstract expressionism.

(click to enlarge) Image courtesy of media.wbur.com.

But while pop art was pro-capitalist, it was also revolutionary in a different sense than traditional Marxism. Pop art sought to democratize the ‘high’ culture of the art world, which had previously been segmented into its own portion of society. We can see evidence for this sort of democratization in Lawrence Alloway’s essay “Arts and the Mass Media” (1958). He concludes,

“… it is no longer sufficient to define culture solely as something that a minority guards for the few and the future (though such art is uniquely valuable and a precious as ever). Our definition of culture is being stretched beyond the fine art limits imposed on it by Renaissance theory, and refers now, increasingly, to the whole complex of human activities.”

Pop art had gone beyond the confines of the art gallery. It had actually began to affect the very media that had influenced it in the first place: advertising. In reference to a pop art marketing campaign, advertising-agency president Ernie Fladell remarked, “sure, we’re using a pop philosophy, but pop is kind of a movement rather than an art thing.. We’ve captured this fun thing that’s happening.” (pg. 141, Doris) The art world had began to eat into popular culture, and if art critics were afraid that pop art was going to ruin ‘high’ art, it may be the case that it actually just improved ‘low’ art. Pop art now constituted the ‘high’ culture of the art world and it was rapidly democratizing the artistic sensibility to the mass culture.

“In August 1965, the Daily News reported on the new pop phenomenon: It’s all part of the new scene in New York- the scene that includes underground movies, wacky fashions and discotheque dancing. It has hit art hard and the art world has exploded, not with a bang but with a Pop- Pop Art, that is. None of these ‘cultural developments’ is isolated… Taken together they add up to a cultural revolution.” (pg. 146, Doris)